Understanding Fungal Nails: What Works, What Doesn’t, and Why

Fungal nail infections are one of the most common problems we see in clinics — and also one of the most frustrating for patients.

Many people arrive having already tried paints, pharmacy treatments, oils or home remedies, often for months or even years. Sometimes the nail improves slightly, sometimes not at all, and very often the problem returns.

This isn’t because people aren’t trying hard enough.

In most cases, it’s because fungal nails are widely misunderstood — particularly in the terms of where the infection actually lives and what needs to be treated for improvement to occur.

The Most Important Thing to Understand

A fungal nail infection is not primarily a problem of the nail itself.

The nail plate — the hard part you can see — is made of dense, dead keratin. It has no blood supply and no ability to heal. In most cases, the infection instead lives in:

the skin of the nail bed

the underside of the nail plate

keratin debris beneath the nail

The nail shows the damage, but for the majority, it is not where the fungus is biologically active.

This distinction underpins why so many treatments fail — and why some work in very specific situations.

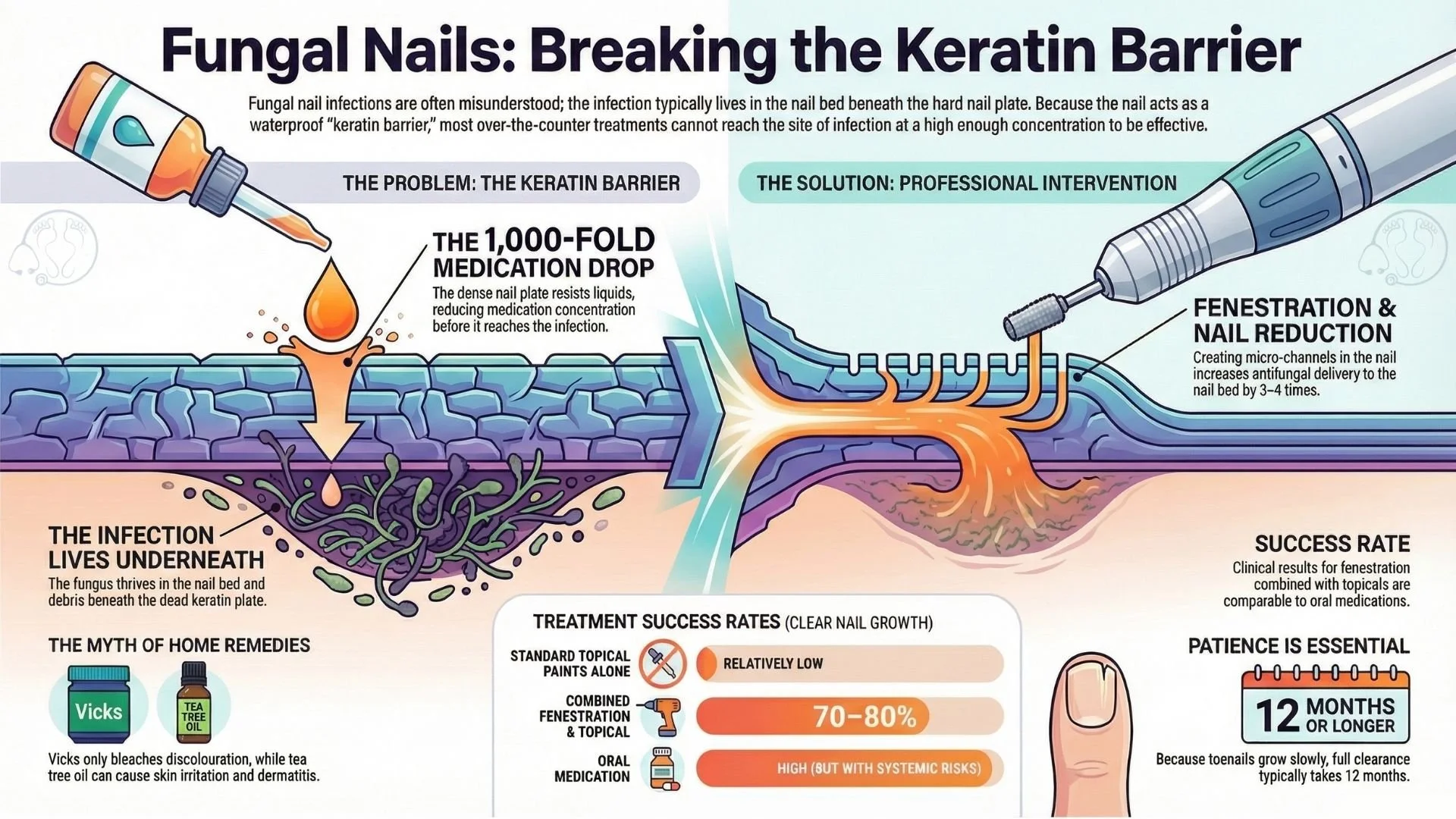

The Problem: The Keratin Barrier

The nail plate is designed to protect the toe, and it does that job extremely well.

Unfortunately, this creates the biggest challenge in fungal nail treatment.

The nail forms a dense, hydrophobic keratin barrier, meaning it strongly resists penetration by liquids and medications. Research shows that when a topical antifungal is applied to the surface of the nail, the concentration of medication can drop by up to 1,000-fold by the time it reaches the nail bed — the true site of infection.

In simple terms:

very little of what you apply actually reaches where the fungus lives.

This explains why many people apply treatments exactly as directed but see little or no lasting improvement.

When Topical Treatments Can Be Effective

It’s important to be clear — topical treatments are not useless. They are simply appropriate for the right type of fungal infection.

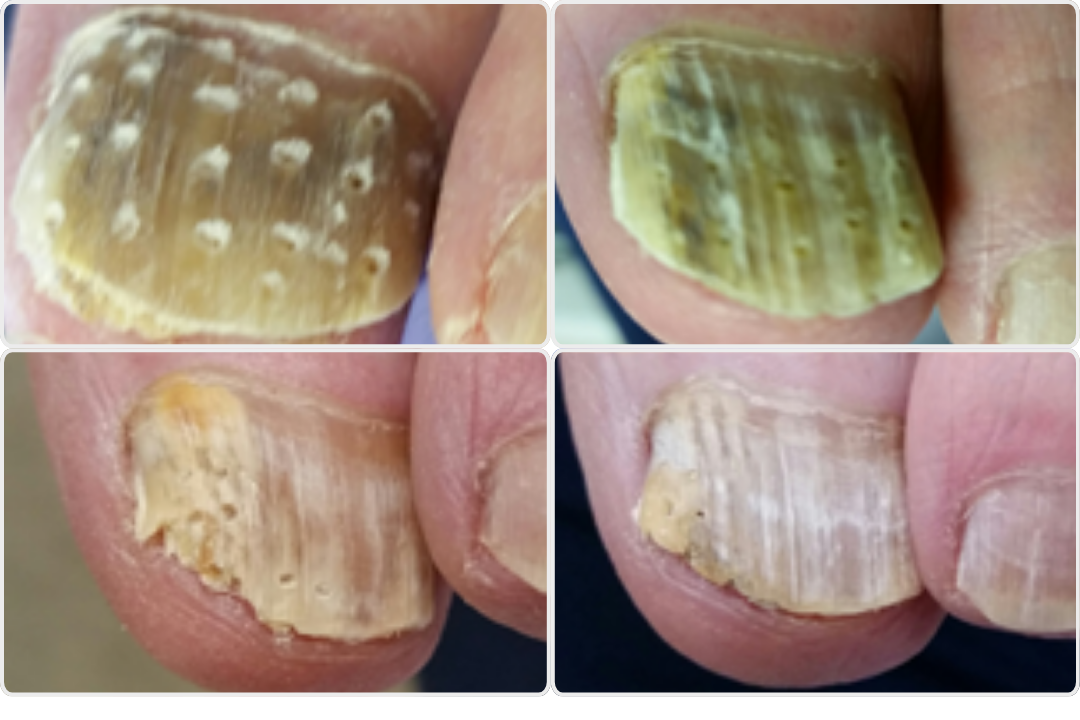

In cases of superficial white onychomycosis, where the infection affects only the outer surface of the nail and appears as white, powdery patches, topical treatments can be effective. In these cases, the fungus is confined to the superficial layers of the nail plate, is considered an early phase of infection and has not invaded the nail bed.

Because the keratin barrier is minimal, antifungal products can reach the affected area more easily, making topical treatment a suitable and often successful option when used consistently.

However, once the infection extends beneath the nail into the nail bed — which is far more common — topical treatments alone are much less effective.

Why Painting the Nail Often Isn’t Enough

For most fungal nail infections, the fungus lives beneath the nail plate. When medication cannot reach the nail bed at a sufficient concentration, the infection can continue even if the nail appears to look better.

Clinically, this is known as failing to reach the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) — the level required to stop fungal growth.

This is why:

the nail may look whiter or clearer

thickness may reduce slightly

improvement stalls or reverses when treatment stops

Why Some Home Remedies Are Not Recommended

Tea tree oil

Tea tree oil is often suggested online, but from a clinical perspective it is not advised.

It is a known skin irritant, particularly around nail folds. Each time the bottle is opened, the oil oxidises, increasing the risk of contact dermatitis. We frequently see patients with redness, soreness or inflamed skin as a result — which can actually compromise the skin barrier and make infection harder to manage.

There is also no reliable evidence that tea tree oil can eradicate fungal nail infection.

Vicks VapoRub

Vicks is another commonly discussed remedy. Some people notice their nails look better when using it.

This improvement is largely cosmetic. Vicks can cause a whitening or bleaching effect of the nail plate, reducing yellow discolouration, but it does not treat the infection living beneath the nail.

The nail may look healthier while the fungus remains active underneath.

Why Nail Reduction and Fenestration Matter

Modern podiatric research increasingly supports one key principle:

treatment is far more effective when the nail barrier is reduced.

By thinning the nail or creating controlled micro-channels through the nail plate (fenestration), medication can bypass the keratin barrier and reach the nail bed directly.

Laboratory studies show that this can increase antifungal delivery to the nail bed by three to four times compared to untreated nails. Clinical studies also demonstrate significantly higher rates of clear nail growth when topical antifungals are combined with controlled nail penetration — with results approaching those of oral medication, but without systemic risks.

This is why professional nail reduction is not cosmetic — it is therapeutic.

Let’s Look At The Statistics

Treatment can be challenging, with recurrence rates of 20–50%, particularly if nail thickness and footwear contamination are not addressed.

Standard topical treatments alone achieve relatively low success rates. However, when treatment is combined with fenestration, studies show clear nail growth in around 70–80% of cases, with outcomes comparable to oral medication but without systemic risks.

Even with effective treatment, toenails grow slowly, meaning full clearance often takes 12 months or longer.

Why Diagnosis Is So Important

Not every thick, discoloured or damaged nail is fungal.

Trauma, footwear pressure, psoriasis and age-related nail changes can closely mimic fungal infection. Research shows that even experienced clinicians cannot always diagnose fungal nails accurately by appearance alone.

Treating a non-fungal nail as if it were fungal inevitably leads to frustration and poor outcomes.

Why Fungal Nails Often Return

Even when treatment is successful, fungal nails have high recurrence rates.

Contributing factors include:

untreated athlete’s foot

contaminated footwear

slow nail growth

reduced circulation

diabetes or immune compromise

fungal biofilms and resistance

Toenails grow slowly — often taking 9 to 18 months to fully replace — and fungal infection can slow this process further.

There are no quick fixes.

What Effective Management Actually Involves

Successful fungal nail management focuses on:

accurate diagnosis

reducing nail thickness

treating the skin and nail bed

consistency over time

moisture and footwear hygiene

realistic expectations

It is not about miracle cures — it is about understanding the biology of the nail and working with it.

A Final Thought

If you’ve been struggling with a fungal nail, it’s important to know this:

Failure is rarely due to lack of effort.

In most cases, treatment hasn’t failed — it simply hasn’t been able to reach the infection.

Once the focus shifts from “painting the nail” to treating the nail bed and addressing the keratin barrier, outcomes improve significantly.

If your nail is changing, thickening or repeatedly deteriorating, professional assessment can help determine whether fungus is truly present and what management approach is most appropriate.

-

Haneke E. Prevention of relapse and re-infection: prophylaxis. In: Rigopoulos D, Elewski B, Richert B (eds). Onychomycosis: Diagnosis and Management. Chichester: Wiley; 2018: 162–171.

Gupta AK, Stec N, Summerbell RC, et al. Onychomycosis: a review. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2020;34(9):1972–1990.

Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Onychomycosis: a review. Journal of Fungi. 2015;1(1):30.

Ameen M, Lear JT, Madan V, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of onychomycosis 2014. British Journal of Dermatology. 2014;171(5):937–958.

Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019;80(4):835–851.

Fletcher CL, Hay RJ, Smeeton NC. Observer agreement in recording the clinical signs of nail disease and the accuracy of clinical diagnosis of fungal and non-fungal nail disease. British Journal of Dermatology. 2003;148(3):558–562.

Tsunemi Y, Takehara K, Oe M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of tinea unguium based on clinical observation. The Journal of Dermatology. 2015;42(3):221–222.

Mareschal A, Scherer E, Lihoreau T, et al. Diagnosis of toenail onychomycosis by an immunochromatographic dermatophyte test strip. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2021;35:e367–e369.

Gupta AK, Wang T, Cooper EA, et al. A comprehensive review of non-dermatophyte mould onychomycosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2023.

Martinez-Rossi NM, Peres NTA, Rossi A. Antifungal resistance mechanisms in dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:369–383.

Bristow IR, et al. Rapid treatment of subungual onychomycosis using controlled micro-nail penetration and terbinafine solution. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2016.

Nett JE, Andes DR. Fungal biofilms: in vivo models for discovery of anti-biofilm drugs. Microbiology Spectrum. 2015;3.

Ghannoum MA, Isham N, Long L. Optimization of an infected shoe model for the evaluation of an ultraviolet shoe sanitizer device. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2012;102(4):309–313.

Bristow IR, Joshi LT. Dermatophyte resistance – on the rise. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2023;16:69.

Na G, Suh M, Sung Y, Choi S. A decreased growth rate of the toenail observed in patients with distal subungual onychomycosis. Annals of Dermatology. 1995;7:217–221.

Gupta AK, Versteeg SG. A critical review of improvement rates for laser therapy used to treat toenail onychomycosis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2017;31:1111–1118.

Gupta AK, Gupta MA, Summerbell RC. The epidemiology of onychomycosis: possible role of smoking and peripheral arterial disease. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2000;14:466–469.

Gupta AK, Konnikov N, MacDonald P, et al. Prevalence and epidemiology of toenail onychomycosis in diabetic subjects. British Journal of Dermatology. 1998;139:665–671.

Gupta AK, Taborda P, Taborda V, et al. Epidemiology and prevalence of onychomycosis in HIV-positive individuals. International Journal of Dermatology. 2000;39:746–753.

Zaias N, Rebell G. Chronic dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996;35(Suppl):S17–S20.

Hay RJ. Genetic susceptibility to dermatophytosis. European Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;8:346–349.

Saner MV, Kulkarni AD, Pardeshi CV. Insights into drug delivery across the nail plate barrier. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2014;22(9):769–789.

Transungual delivery of ciclopirox is increased 3–4-fold by mechanical fenestration. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(1):27. (PMC6358885)